Dafen oil painting Village

From Copies to Creativity: How Dafen Village Is Reinventing Itself

Back in August 2014, a bus carrying 18 members of the U.S. House of Representatives quietly pulled up at Dafen Art Museum in Shenzhen. But instead of touring the museum’s landscape oil painting exhibition, the group insisted on walking the streets of Dafen Village alone—no guides, no local officials, just wandering every alley and corner on their own. They didn’t explain why they came, and after just a few hours, they were gone. Mysterious, to say the least.

While officials treated it as a routine visit from foreign guests, word quickly spread that this might not have been just sightseeing. Some insiders suspected the real reason was to investigate possible copyright infringement in the village. In fact, just days before their arrival, local authorities had already conducted their own sweep of the area—just in case.

Interestingly, the U.S. delegates didn’t find anything suspicious during their walk-through. Some even bought paintings that were claimed to be original. This outcome was unexpected, especially considering Dafen’s long-standing reputation as a place for art reproduction. That’s what sparked curiosity: had Dafen really changed?

Historically, Dafen wasn’t always an art village. It was just a small, quiet Hakka settlement. Everything changed when Hong Kong art dealer Huang Jiang showed up in the late ’80s. He was a former welder turned artist who started receiving huge commercial orders for oil paintings—often from retail giants like Walmart. Huang relocated his operations from Hong Kong to Shenzhen, then eventually settled in the sleepy village of Dafen due to low rent and policy incentives.

He brought in 26 painters and started what would become China’s most famous oil painting village. At its peak, Dafen was producing hundreds of thousands of paintings, mostly replicas, using an efficient assembly-line method. One painter would specialize in skies, another in water, and so on. It was low-cost, high-volume, and very successful. By the early 2000s, the village was churning out over a million artworks annually.

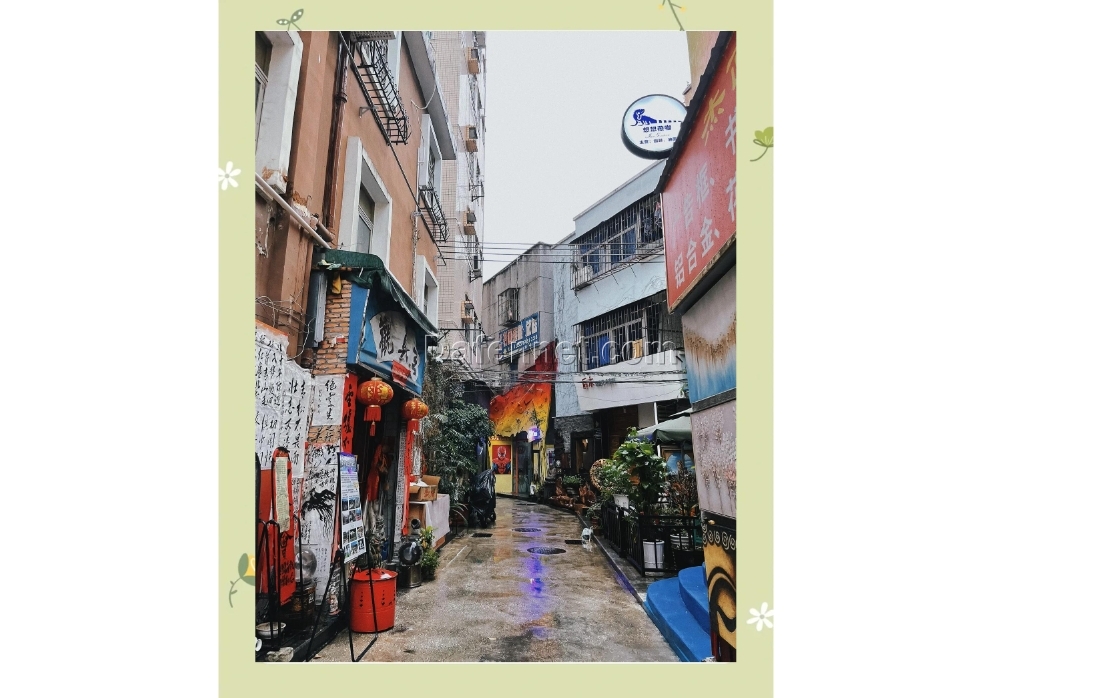

As demand grew, so did the village—turning into a buzzing art hub with over 1,200 galleries and studios. But as its fame spread, so did criticism, especially from abroad. Dafen became known for copycat art, and that’s likely what triggered the interest of U.S. officials.

But Dafen’s real challenge wasn’t just legal or ethical—it was economic. The art reproduction industry, originally shifted to China due to low costs, was now moving on to even cheaper markets like Vietnam and Malaysia. If Dafen didn’t adapt, it risked becoming obsolete.

So now, Dafen is trying to pivot—shifting from reproductions to original art, from mass production to creative expression. The future of the village depends on embracing originality and intellectual property. It’s no longer about being the cheapest, but about offering something unique that can’t be copied elsewhere.

As one local leader put it: “If we keep playing the price game, we’ll lose. Our only way forward is with true, original art.”